Detroit

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (December 2024) |

Detroit | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Etymology: French: détroit (strait) | |

| Nicknames: The Motor City, Motown, and others | |

| Motto(s): Speramus Meliora; Resurget Cineribus (Latin: We Hope For Better Things; It Shall Rise From the Ashes) | |

Interactive map of Detroit | |

| Coordinates: 42°20′N 83°03′W / 42.333°N 83.050°W[1] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Wayne |

| Founded (Fort Detroit) | July 24, 1701 |

| Incorporated a | September 13, 1806 |

| Founded by | Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac (1658-1730) & Alphonse de Tonty (1659-1727) |

| Named for | Detroit River |

| Government | |

| • Type | Strong Mayor |

| • Body | Detroit City Council |

| • Mayor | Mike Duggan (I) |

| • Clerk | Janice Winfrey |

| • City council | Members

|

| Area | |

• City | 142.89 sq mi (370.09 km2) |

| • Land | 138.73 sq mi (359.31 km2) |

| • Water | 4.16 sq mi (10.78 km2) |

| • Urban | 1,284.8 sq mi (3,327.7 km2) |

| • Metro | 3,888.4 sq mi (10,071 km2) |

| Elevation | 656 ft (200 m) |

| Population | |

• City | 639,111 |

• Estimate (2023)[4] | 633,218 |

| • Rank | 78th in North America 26th in the United States 1st in Michigan |

| • Density | 4,606.84/sq mi (1,778.71/km2) |

| • Urban | 3,776,890 (US: 12th) |

| • Urban density | 2,939.6/sq mi (1,135.0/km2) |

| • Metro | 4,365,205 (US: 14th) |

| Demonym | Detroiter |

| GDP | |

| • MSA | $305.412 billion (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 482XX |

| Area code | 313 |

| FIPS code | 26-22000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1617959[1] |

| Major airports | Detroit Metropolitan Airport, Coleman A. Young International Airport |

| Mass transit | Detroit Department of Transportation, Detroit People Mover, QLine |

| Website | detroitmi |

Detroit (/dɪˈtrɔɪt/ ⓘ dih-TROYT, locally also /ˈdiːtrɔɪt/ DEE-troyt)[8] is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is the largest U.S. city on the Canadian border and the county seat of Wayne County. Detroit had a population of 639,111 at the 2020 census,[9] making it the 26th-most populous city in the United States. The Metro Detroit area, home to 4.3 million people, is the second-largest in the Midwest after the Chicago metropolitan area and the 14th-largest in the United States. A significant cultural center, Detroit is known for its contributions to music, art, architecture and design, in addition to its historical automotive background.[10][11]

In 1701, Royal French explorers Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac (1658–1730), and Alphonse de Tonty (1659–1727), founded Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit. During the late 19th and early 20th century, it became an important industrial hub at the center of the Great Lakes region in the Midwestern United States. The city's population rose to be the fourth-largest in the nation by 1920, after New York City, Chicago, and Philadelphia, with the expansion of the automotive industry in the early 20th century.[12] One of its main features, the Detroit River, became the busiest commercial hub in the world—carrying over 65 million tons of shipping commerce each year. In the mid-20th century, Detroit entered a state of urban decay which has continued to the present, as a result of industrial restructuring, the loss of jobs in the auto industry, and rapid suburbanization. Since reaching a peak of 1.85 million at the 1950 census, Detroit's population has declined by more than 65 percent.[9] In 2013, Detroit became the largest U.S. city to file for bankruptcy, but successfully exited in December 2014.[13]

Detroit is a port on the Detroit River, one of the four major straits that connect the Great Lakes system to the St. Lawrence Seaway. The city anchors the third-largest regional economy in the Midwest and the 16th-largest in the United States.[14] It is also best known as the center of the U.S. automotive industry, and the "Big Three" auto manufacturers—General Motors, Ford, and Stellantis North America (Chrysler)—are all headquartered in Metro Detroit.[15] It houses the Detroit Metropolitan Airport, one of the most important hub airports in the United States. Detroit and its neighboring Canadian city Windsor constitute the second-busiest international crossing in North America, after San Diego–Tijuana.[16]

Detroit's culture is marked with diversity, having both local and international influences. Detroit gave rise to the music genres of Motown and techno, and also played an important role in the development of jazz, hip-hop, rock, and punk. A globally unique stock of architectural monuments and historic places was the result of the city's rapid growth in its boom years. Since the 2000s, conservation efforts have managed to save many architectural pieces and achieve several large-scale revitalizations, including the restoration of several historic theaters and entertainment venues, high-rise renovations, new sports stadiums, and a riverfront revitalization project. Detroit is an increasingly popular tourist destination which caters to about 16 million visitors per year.[17] In 2015, Detroit was given a name called "City of Design" by UNESCO, the first and only U.S. city to receive that designation.[18]

History

[edit]Toponymy

[edit]

Detroit is named after the Detroit River, connecting Lake Huron with Lake Erie. The name comes from the French language word détroit meaning 'strait' as the city was situated on a narrow north–south passage of water linking the two lakes. The river was known as le détroit du Lac Érié in the French language, which means 'the strait of Lake Erie'.[19][20] In the historical context, the strait included the St. Clair River, Lake St. Clair, and the Detroit River.[21][22]

Early settlement

[edit]

Kingdom of France 1701–1760

Kingdom of Great Britain 1760–1796

United States 1796–1812

United Kingdom 1812–1813

United States 1813–present

Paleo-Indians inhabited areas near Detroit as early as 11,000 years ago including the culture referred to as the Mound Builders.[23] By the 17th century, the region was inhabited by Huron, Odawa, Potawatomi, and Iroquois peoples.[24] The area is known by the Anishinaabe people as Waawiiyaataanong, translating to 'where the water curves around'.[25]

The first Europeans did not penetrate into the region and reach the straits of Detroit until French missionaries and traders worked their way around the Iroquois League, with whom they were at war in the 1630s.[26] The Huron and Neutral people held the north side of Lake Erie until the 1650s, when the Iroquois pushed them and the Erie people away from the lake and its beaver-rich feeder streams in the Beaver Wars of 1649–1655.[26] By the 1670s, the war-weakened Iroquois laid claim to as far south as the Ohio River valley in northern Kentucky as hunting grounds,[26] and had absorbed many other Iroquoian peoples after defeating them in war.[26] For the next hundred years, virtually no British or French action was contemplated without consultation with the Iroquois or consideration of their likely response.[26]

French settlement

[edit]

On July 24, 1701, the French explorer Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac (1658–1730), with his lieutenant Alphonse de Tonty (1659–1727), and more than a hundred other Royal French settlers traveling south and west from New France (modern Province of Quebec), along the St. Lawrence River valley to the Great Lakes region, began constructing a small fort on the north bank of the Detroit River. Cadillac named the settlement Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit,[27] after Louis Phélypeaux, comte de Pontchartrain (1643–1727), the Secretary of State of the Navy under King Louis XIV (1638–1715, reigned 1643–1718) in the Royal government in Paris.[28] Sainte-Anne-de-Détroit was founded on July 26 and is the second-oldest continuously operating Roman Catholic parish in the United States.[29] France offered free land to colonists to attract families further west into the Great Lakes region interior of the North American continent to Detroit; when it eventually reached a population of about 800 by 1765, after the colonial conflict of the French and Indian War (1753–1763), (Seven Years' War in Europe), it became the largest European settlement between the important towns of Montreal and New Orleans, both also French settlements, in the former colonies of New France and La Louisiane (further south on the Mississippi River, on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico), respectively.[30]

British rule

[edit]During the French and Indian War (1753–63)—the North American front of the Seven Years' War in Europe between the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of France—British troops gained control of the settlement a few years into the conflict in 1760 and shortened its name to Detroit. Several regional Native American tribes, such as the Potowatomi, Ojibwe and Huron, launched Pontiac's War (1763–1766), and laid siege in 1763 to Fort Detroit along the Detroit River in the Great Lakes but failed to capture it. In defeat, France ceded its territory in North America of New France and south of the lakes east of the Mississippi to the Appalachian Mountains to Britain following the war.[31]

When Great Britain evicted France from its colonial possessions in New France (Canada) in the peace terms of the Treaty of Paris of 1763, it also removed one barrier to American colonists migrating west across the mountains.[32] British negotiations with the Iroquois would both prove critical and lead to the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which limited settlements South of and below the Great Lakes and west of the Alleghenies / Appalachians. Many colonists and pioneers in the Thirteen Colonies along the East Coast, resented and then simply defied this restraint, later becoming supporters of the rebellious American Revolution. By 1773, after the addition of increasing numbers of the Anglo-American settlers, the population of Detroit and Fort Detroit, was edging up to 1,400 (doubled in the previous decade). During the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), the indigenous and loyalist raids of 1778 and the resultant 1779 decisive Sullivan Expedition reopened the Ohio Country (north of the Ohio River and west of the mountains) to even more westward emigration, which began almost immediately to get away from the eastern warfare. By 1778, its population had doubled again, reaching 2,144 and it was the third-largest town in what was known then as the Province of Quebec since the British takeover of former French colonial possessions in North America in 1763.[33]

After the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) and the establishment and recognition of the United States as an independent country, Britain (United Kingdom) ceded Detroit and other territories in the interior region of the continent, south of the Great Lakes and west of the Appalachian Mountains chain to the Mississippi River under the peace of the terms of the 1783 Treaty of Paris, which established the southern border with its still continuing colonial provinces of what remained of British North America, later provinces of Upper Canada and Lower Canada. However, the disputed border area remained under British control with several military forts and trading posts for another decade, and its forces did not fully withdraw until 1796, following the negotiations and ratification of the subsequent Jay Treaty of 1794 between the British and Americans.[34] By the turn of the 19th century, white American settlers began pouring westwards across the Appalachians and through the Great Lakes.[35]

The region's then colonial economy was based on the lucrative fur trade, in which numerous Native American people had important roles as trappers and traders. Today the municipal flag of Detroit reflects its both its French and English colonial heritage. Descendants of the earliest French and French-Canadian settlers formed a cohesive community, who gradually were superseded as the dominant population after more Anglo-American settlers arrived in the early 19th century with American westward migration. Living along the shores of Lake St. Clair and south to Monroe and downriver suburbs, the ethnic French Canadians of Detroit, also known as Muskrat French in reference to the fur trade, remain a subculture in the region up into the 21st century.[36][37]

19th century

[edit]The Great Detroit Fire of 1805 destroyed most of the Detroit settlement, which had primarily buildings made of wood. One stone fort, a river warehouse, and brick chimneys of former wooden homes were the sole structures to survive.[38] Of the 600 Detroit residents in this area, none died in the fire.[39] The legacy of the fire of 1805 lives on in many aspects of modern Detroit heritage. The cities motto, "Speramus Meliora; Resurget Cineribus" was coined by Roman Catholic priest Father Gabriel Richard (1767–1832), as he looked out at the ruins of the city in the fire's aftermath.[40][41] The city seal, designed by J.O. Lewis in 1827, directly depicts the Great Fire of 1805. Two women stand in the foreground while on the left, the city burns in the background and a woman weeps over the destruction. The woman on the right consoles her by gesturing to a new city that will rise in its place.[42] The city seal also forms the center of the flag of the city.

From 1805 to 1847, Detroit was the territorial capital city of the old federal Michigan Territory (1805–1837), and later first state capital, in January 1837, when after 32 years, the old federal territory was admitted by act of the United States Congress and approved by seventh President Andrew Jackson (1769–1845, served 1829–1837), as the 26th state to the federal Union on its northern border.

William Hull (1753–1825), the United States Army elderly commander at Fort Detroit, surrendered without a fight to attacking British Army troops from adjacent Upper Canada in the northeast and their Native American allies laying siege during the first months of the War of 1812 (1812–1815) in the siege of Detroit in mid-August 1812, only two months after the Congress in Washington declared war. He was fooled and led to believing his forces were vastly outnumbered by the attacking / surrounding "Redcoats". Five months later in the conflict, the Battle of Frenchtown in January 1813, was part of a U.S. military effort to retake the fort and town, and U.S. troops suffered their highest number of fatalities of any battle in the so-called Second War for Independence. This battle is commemorated at the nearby River Raisin National Battlefield Park south of Detroit in Monroe County. Detroit was eventually recaptured by the strengthened and better prepared United States military forces later that year.[43]

The settlement was incorporated as a city in 1815.[44] As the city expanded, a radial geometric street plan with a logical grid and broad avenues, developed by U.S. Judge for the old Michigan Territory (Chief Justice) Augustus B. Woodward (1774–1827, served 1805–1824), was followed (where Detroit gets its namesake and major downtown street of Woodward Avenue), featuring grand boulevards and plazas, inspired and influenced by the design of the American federal national capital city of Washington, D.C. in the 1790s by French engineer and architect, Pierre L'Enfant, plus a later example as later laid out across the Atlantic Ocean by the Emperor Napoleon I (Napoleon Bonaparte) in the capital city of Paris in his First French Empire (France) to improve and transform the old Middle Ages / medieval city of Europe, and subsequently further developed by his nephew and later successor Emperor Napoleon III in the 1850s.[45] In 1817, Woodward went on to establish the Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania in the city. Intended to be a centralized system of schools, libraries, and other cultural and scientific institutions for the old federal Michigan Territory (1805–1837), the Catholepistemiad evolved into the modern University of Michigan at Ann Arbor.

Prior to the American Civil War 1861–1865), the city's access to the Canada–U.S. international border made it a key stop for refugee slaves gaining freedom in the North along the Underground Railroad. Many simply went further north across the Detroit River to Canada to escape pursuit by rampaging Southern slave catchers.[46][44] An estimated 20,000 to 30,000 African-American refugees settled in Canada.[47] Two prominent African American activists and abolitionists George DeBaptiste (c.1815-1875), was considered to be the "president" of the Detroit Underground Railroad, William Lambert (1817–1890), the "vice president" or "secretary", plus the elderly Quaker white woman Laura Smith Haviland (1808–1898), the "superintendent".[48]

Numerous men from Detroit volunteered to fight for the Federal Union and enlisted in its Union Army (United States Army) during the American Civil War, including the 24th Michigan Infantry Regiment. It was part of the famous Iron Brigade, which fought with distinction and suffered 82% casualties at the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863. When the First Volunteer Infantry Regiment arrived to fortify the federal national capital city of Washington, D.C. in the early days of the War in April 1861, newly elected and inaugurated 16th President Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865, served 1861–1865), was quoted as saying, "Thank God for Michigan!!" George Armstrong Custer (1839–1876), led the Michigan Brigade during the Civil War and called them the "Wolverines".[49] The city's tensions over race, and nationally, the draft led to the Detroit race riot of 1863, in which violence erupted, leaving some dead and over 200 Black residents homeless. This prompted the establishment of a full-time police force in 1865.

During the late 19th century, wealthy industry and shipping magnates commissioned the design and construction of several Gilded Age mansions east and west of the current downtown, along the major avenues of the Woodward plan. Most notable among them was the David Whitney House at 4421 Woodward Avenue, and the grand avenue became a favored address for mansions. During this period, some referred to Detroit as the "Paris of the West" for its architecture, grand avenues in the Paris style, and for Washington Boulevard, recently electrified by Thomas Edison.[44] The city had grown steadily from the 1830s with the rise of shipping, shipbuilding, and manufacturing industries. Strategically located along the Great Lakes waterway, Detroit emerged as a major port and transportation hub. [citation needed]

In 1896, a thriving carriage trade prompted Henry Ford to build his first automobile in a rented workshop on Mack Avenue. During this growth period, Detroit expanded its borders by annexing all or part of several surrounding villages and townships.[50]

20th century

[edit]In 1903, Henry Ford founded the Ford Motor Company. Ford's manufacturing—and those of automotive pioneers William C. Durant, Horace and John Dodge, James and William Packard, and Walter Chrysler—established the Big Three automakers and cemented Detroit's status in the early 20th century as the world's automotive capital.[44] The growth of the auto industry was reflected by changes in businesses throughout the Midwest and nation, with the development of garages to service vehicles and gas stations, as well as factories for parts and tires.[citation needed] Because of the booming auto industry, Detroit became the fourth-largest city in the nation by 1920, following New York City, Chicago, and Philadelphia.[51]

In 1907, the Detroit River carried 67,292,504 tons of shipping commerce through Detroit to locations all over the world. For comparison, London shipped 18,727,230 tons, and New York shipped 20,390,953 tons. The river was dubbed "the Greatest Commercial Artery on Earth" by The Detroit News in 1908. The prohibition of alcohol from 1920 to 1933 resulted in the Detroit River becoming a major conduit for smuggling of illegal Canadian spirits.[12]

With the rapid growth of industrial workers in the auto factories, labor unions such as the American Federation of Labor and the United Auto Workers (UAW) fought to organize workers to gain them better working conditions and wages. They initiated strikes and other tactics in support of improvements such as the 8-hour day/40-hour work week, increased wages, greater benefits, and improved working conditions. The labor activism during those years increased the influence of union leaders in the city such as Jimmy Hoffa of the Teamsters and Walter Reuther of the UAW.[52]

Detroit, like many places in the United States, developed racial conflict and discrimination in the 20th century following the rapid demographic changes as hundreds of thousands of new workers were attracted to the industrial city. The Great Migration brought rural blacks from the South; they were outnumbered by southern whites who also migrated to the city. Immigration brought southern and eastern Europeans of Catholic, Jewish, and Orthodox Christian faith; these new groups competed with native-born whites for jobs and housing in the booming city.[citation needed]

Detroit was one of the major Midwest cities that was a site for the dramatic urban revival of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) beginning in 1915. "By the 1920s the city had become a stronghold of the KKK", whose members primarily opposed Catholic and Jewish immigrants but also practiced discrimination against Black Americans.[53] Even after the decline of the KKK in the late 1920s, the Black Legion, a secret vigilante group, was active in the Detroit area in the 1930s. One-third of its estimated 20,000 to 30,000 members in Michigan were based in the city. It was defeated after numerous prosecutions following the kidnapping and murder in 1936 of Charles Poole, a Catholic organizer with the federal Works Progress Administration. Some 49 men of the Black Legion were convicted of numerous crimes, with many sentenced to life in prison for murder.[54]

By 1940, 80% of Detroit deeds contained restrictive covenants prohibiting African Americans from buying houses they could afford. These discriminatory tactics were successful as a majority of black people in Detroit resorted to living in all-black neighborhoods such as Black Bottom and Paradise Valley. At this time, white people still made up about 90.4% of the city's population.[55] White residents attacked black homes: breaking windows, starting fires, and detonating bombs.[56][57]

World War II

[edit]In the 1940s the world's "first urban depressed freeway" ever built, the Davison,[58] was constructed. During World War II, the government encouraged retooling of the American automobile industry in support of the Allied powers, leading to Detroit's key role in the American Arsenal of Democracy.[59] Jobs expanded so rapidly due to the defense buildup in World War II that 400,000 people migrated to the city from 1941 to 1943, including 50,000 blacks in the second wave of the Great Migration, and 350,000 whites, many of them from the South. Whites, including ethnic Europeans, feared black competition for jobs and scarce housing. The federal government prohibited discrimination in defense work, but when in June 1943 Packard promoted three black people to work next to whites on its assembly lines, 25,000 white workers walked off the job.[60] The 1943 Detroit race riot took place in June, three weeks after the Packard plant protest, beginning with an altercation at Belle Isle. A total of 34 people were killed, 25 of them black and most at the hands of the white police force, while 433 were wounded (75% of them black), and property valued at $2 million (worth $30.4 million in 2020) was destroyed. Rioters moved through the city, and young whites traveled across town to attack more settled blacks in their neighborhood of Paradise Valley.[61][62]

Postwar era

[edit]Industrial mergers in the 1950s, especially in the automobile sector, increased oligopoly in the American auto industry. Detroit manufacturers such as Packard and Hudson merged into other companies and eventually disappeared. At its peak population of 1,849,568, in the 1950 Census, the city was the fifth-largest in the United States.[63]

In this postwar era, the auto industry continued to create opportunities for many African Americans from the South, who continued with their Great Migration to Detroit and other northern and western cities to escape the strict Jim Crow laws and racial discrimination policies of the South. Postwar Detroit was a prosperous industrial center of mass production. The auto industry comprised about 60% of all industry in the city, allowing space for a plethora of separate booming businesses including stove making, brewing, furniture building, oil refineries, pharmaceutical manufacturing, and more. The expansion of jobs created unique opportunities for black Americans, who saw novel high employment rates: there was a 103% increase in the number of blacks employed in postwar Detroit. Black Americans who immigrated to northern industrial cities from the south still faced intense racial discrimination in the employment sector. Racial discrimination kept the workforce and better jobs predominantly white, while many black Detroiters held lower-paying factory jobs. Despite changes in demographics as the city's black population expanded, Detroit's police force, fire department, and other city jobs continued to be held by predominantly white residents. This created an unbalanced racial power dynamic.[64]

Unequal opportunities in employment resulted in unequal housing opportunities for the majority of the black community: with overall lower incomes and facing the backlash of discriminatory housing policies, the black community was limited to lower cost, lower quality housing in the city. The surge in the black population augmented the strain on housing scarcity. The livable areas available to the black community were limited, and as a result, families often crowded together in unsanitary, unsafe, and illegal quarters. Such discrimination became increasingly evident in the policies of redlining implemented by banks and federal housing groups, which almost completely restricted the ability of blacks to improve their housing and encouraged white people to guard the racial divide that defined their neighborhoods. As a result, black people were often denied bank loans to obtain better housing, and interest rates and rents were unfairly inflated to prevent their moving into white neighborhoods. White residents and political leaders largely opposed the influx of black Detroiters to white neighborhoods, believing that their presence would lead to neighborhood deterioration. This perpetuated a cyclical exclusionary process that marginalized the agency of black Detroiters by trapping them in the unhealthiest, least safe areas of the city.[64]

As in other major American cities in the postwar era, modernist planning ideology drove the construction of a federally subsidized, extensive highway and freeway system around Detroit, and pent-up demand for new housing stimulated suburbanization; highways made commuting by car for higher-income residents easier. However, this construction had negative implications for many lower-income urban residents. Highways were constructed through and completely demolished neighborhoods of poor residents and black communities who had less political power to oppose them. The neighborhoods were mostly low income, considered blighted, or made up of older housing where investment had been lacking due to racial redlining, so the highways were presented as a kind of urban renewal. These neighborhoods (such as Black Bottom and Paradise Valley) were extremely important to the black communities of Detroit, providing spaces for independent black businesses and social/cultural organizations. Their destruction displaced residents with little consideration of the effects of breaking up functioning neighborhoods and businesses.[64]

In 1956, Detroit's last heavily used electric streetcar line, which traveled along the length of Woodward Avenue, was removed and replaced with gas-powered buses. It was the last line of what had once been a 534-mile network of electric streetcars. In 1941, at peak times, a streetcar ran on Woodward Avenue every 60 seconds.[65][66]

All of these changes in the area's transportation system favored low-density, auto-oriented development rather than high-density urban development. Industry also moved to the suburbs, seeking large plots of land for single-story factories. By the 21st century, the metro Detroit area had developed as one of the most sprawling job markets in the United States; combined with poor public transport, this resulted in many new jobs being beyond the reach of urban low-income workers.[67]

In 1950, the city held about one-third of the state's population. Over the next 60 years, the city's population declined to less than 10 percent of the state's population. During the same time period, the sprawling metropolitan area grew to contain more than half of Michigan's population.[44] The shift of population and jobs eroded Detroit's tax base.[citation needed]

In June 1963, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. gave a major speech as part of a civil rights march in Detroit that foreshadowed his "I Have a Dream" speech in Washington, D.C., two months later. While the civil rights movement gained significant federal civil rights laws in 1964 and 1965, longstanding inequities resulted in confrontations between the police and inner-city black youth who wanted change.[68]

I have a dream this afternoon that my four little children, that my four little children will not come up in the same young days that I came up within, but they will be judged on the basis of the content of their character, not the color of their skin ... I have a dream this evening that one day we will recognize the words of Jefferson that "all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness." I have a dream ...

Longstanding tensions in Detroit culminated in the Twelfth Street riot in July 1967. Governor George W. Romney ordered the Michigan National Guard into Detroit, and President Lyndon B. Johnson sent in U.S. Army troops. The result was 43 dead, 467 injured, over 7,200 arrests, and more than 2,000 buildings destroyed, mostly in black residential and business areas. Thousands of small businesses closed permanently or relocated to safer neighborhoods. The affected district lay in ruins for decades.[70] According to the Chicago Tribune, it was the 3rd most costly riot in the United States.[71]

On August 18, 1970, the NAACP filed suit against Michigan state officials, including Governor William Milliken, charging de facto public school segregation. The NAACP argued that although schools were not legally segregated, the city of Detroit and its surrounding counties had enacted policies to maintain racial segregation in public schools. The NAACP also suggested a direct relationship between unfair housing practices and educational segregation, as the composition of students in the schools followed segregated neighborhoods.[72] The District Court held all levels of government accountable for the segregation in its ruling. The Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed some of the decision, holding that it was the state's responsibility to integrate across the segregated metropolitan area.[73] The U.S. Supreme Court took up the case February 27, 1974.[72] The subsequent Milliken v. Bradley decision had nationwide influence. In a narrow decision, the Supreme Court found schools were a subject of local control, and suburbs could not be forced to aid with the desegregation of the city's school district.[74]

"Milliken was perhaps the greatest missed opportunity of that period", said Myron Orfield, professor of law at the University of Minnesota Law School. "Had that gone the other way, it would have opened the door to fixing nearly all of Detroit's current problems."[75] John Mogk, a professor of law and an expert in urban planning at Wayne State University Law School in Detroit, says,

Everybody thinks that it was the riots [in 1967] that caused the white families to leave. Some people were leaving at that time but, really, it was after Milliken that you saw mass flight to the suburbs. If the case had gone the other way, it is likely that Detroit would not have experienced the steep decline in its tax base that has occurred since then.[75]

1970s and decline

[edit]

In November 1973, the city elected Coleman Young as its first black mayor. After taking office, Young emphasized increasing racial diversity in the police department, which was predominantly white.[76] Young also worked to improve Detroit's transportation system, but the tension between Young and his suburban counterparts over regional matters was problematic throughout his mayoral term.

In 1976, the federal government offered $600 million (~$2.5 billion in 2023) for building a regional rapid transit system, under a single regional authority.[77] But the inability of Detroit and its suburban neighbors to solve conflicts over transit planning resulted in the region losing the majority of funding for rapid transit.[citation needed] The city then moved forward with construction of the elevated downtown circulator portion of the system, which became known as the Detroit People Mover.[78]

The gasoline crises of 1973 and 1979 affected auto industry. Buyers chose smaller, more fuel-efficient cars made by foreign makers as the price of gas rose. Efforts to revive the city were stymied by the struggles of the auto industry, as their sales and market share declined. Automakers laid off thousands of employees and closed plants in the city, further eroding the tax base. To counteract this, the city used eminent domain to build two large new auto assembly plants in the city.[79]

Young sought to revive the city by seeking to increase investment in the city's declining downtown. The Renaissance Center, a mixed-use office and retail complex, opened in 1977. This group of skyscrapers was an attempt to keep businesses in downtown.[44][80][81] Young also gave city support to other large developments to attract middle and upper-class residents back to the city. Despite the Renaissance Center and other projects, the downtown area continued to lose businesses to the automobile-dependent suburbs. Major stores and hotels closed, and many large office buildings went vacant. Young was criticized for being too focused on downtown development and not doing enough to lower the city's high crime rate and improve city services to residents.[citation needed]

High unemployment was compounded by middle-class flight to the suburbs, and some residents leaving the state to find work. The result for the city was a higher proportion of poor in its population, reduced tax base, depressed property values, abandoned buildings, abandoned neighborhoods, and high crime rates.[82]

On August 16, 1987, Northwest Airlines Flight 255 crashed near Detroit Metro airport, killing all but one of the 155 people on board, as well as two people on the ground.[83]

In 1993, Young retired as Detroit's longest-serving mayor, deciding not to seek a sixth term, with Dennis Archer succeeding him. Archer prioritized downtown development, easing tensions with its suburban neighbors. A referendum to allow casino gambling in the city passed in 1996; several temporary casino facilities opened in 1999, and permanent downtown casinos with hotels opened in 2007–08.[84]

21st century

[edit]Campus Martius, a reconfiguration of downtown's main intersection as a new park, was opened in 2004. The park has been cited as one of the best public spaces in the United States.[85][86][87] In 2001, the first portion of the International Riverfront redevelopment was completed as a part of the city's 300th-anniversary celebration.[88]

In September 2008, Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick (who had served for six years) resigned following felony convictions. In 2013, Kilpatrick was convicted on 24 federal felony counts, including mail fraud, wire fraud, and racketeering,[89] and was sentenced to 28 years in federal prison.[90] The former mayor's activities cost the city an estimated $20 million.[91] Roughly half of the owners of Detroit's 305,000 properties failed to pay their 2011 tax bills, resulting in about $246 million (~$329 million in 2023) in taxes and fees going uncollected, nearly half of which was due to Detroit. The rest of the money would have been earmarked for Wayne County, Detroit Public Schools, and the library system.[92]

The city's financial crisis resulted in Michigan taking over administrative control of its government.[93] Governor Rick Snyder declared a financial emergency in March 2013, stating the city had a $327 million budget deficit and faced more than $14 billion in long-term debt. It had been making ends meet on a month-to-month basis with the help of bond money held in a state escrow account and had instituted mandatory unpaid days off for many city workers. Those troubles, along with underfunded city services, such as police and fire departments, and ineffective turnaround plans from Mayor Bing and the City Council[94] led the state of Michigan to appoint an emergency manager for Detroit. On June 14, 2013, Detroit defaulted on $2.5 billion of debt by withholding $39.7 million in interest payments, while Emergency Manager Kevyn Orr met with bondholders and other creditors in an attempt to restructure the city's $18.5 billion debt and avoid bankruptcy.[95] On July 18, 2013, Detroit became the largest U.S. city to file for bankruptcy.[96] It was declared bankrupt by U.S. District Court on December 3, with its $18.5 billion debt.[97] On November 7, 2014, the city's plan for exiting bankruptcy was approved. On December 11 the city officially exited bankruptcy. The plan allowed the city to eliminate $7 billion in debt and invest $1.7 billion into improved city services.[98]

One way the city obtained this money was through the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA). Holding over 60,000 pieces of art worth billions of dollars, some saw it as the key to funding this investment. The city came up with a plan to monetize the art and sell it, leading to the DIA becoming a private organization. After months of legal battles, the city finally got hundreds of millions of dollars towards funding a new Detroit.[99]

One of the largest post-bankruptcy efforts to improve city services has been to fix the city's broken street lighting system. At one time it was estimated that 40% of lights were not working, which resulted in public safety issues and abandonment of housing. The plan called for replacing outdated high-pressure sodium lights with 65,000 LED lights. Construction began in late 2014 and finished in December 2016; Detroit is the largest U.S. city with all LED street lighting.[100]

In the 2010s, several initiatives were taken by Detroit's citizens and new residents to improve the cityscape by renovating and revitalizing neighborhoods. Such projects include volunteer renovation groups[101] and various urban gardening movements.[102] Miles of associated parks and landscaping have been completed in recent years. In 2011, the Port Authority Passenger Terminal opened, with the riverwalk connecting Hart Plaza to the Renaissance Center.[81]

One symbol of the city's decades-long decline, the Michigan Central Station, was long vacant. The city renovated it with new windows, elevators and facilities, completing the work in December 2015.[104] In 2018, Ford Motor Company purchased the building and plans to use it for mobility testing with a potential return of train service.[105] Several other landmark buildings have been privately renovated and adapted as condominiums, hotels, offices, or for cultural uses. Detroit was mentioned as a city of renaissance and has reversed many of the trends of the prior decades.[106][107]

The city has seen a rise in gentrification.[108] In downtown, for example, the construction of Little Caesars Arena brought with it high class shops and restaurants along Woodward Avenue. Office tower and condominium construction has led to an influx of wealthy families but also a displacement of long-time residents and culture.[109][110] Areas outside of downtown and other recently revived areas have an average household income of about 25% less than the gentrified areas, a gap that is continuing to grow.[111] Rents and cost of living in these gentrified areas rise every year, pushing minorities and the poor out, causing more and more racial disparity and separation in the city. In 2019, the cost of a one-bedroom loft in Rivertown reached $300,000 (~$352,668 in 2023), with a five-year sale price change of over 500% and average income rising by 18%.[112][better source needed]

Geography

[edit]

Metropolitan area

[edit]Detroit is the center of a three-county urban area (with a population of 3,734,090 within an area of 1,337 square miles (3,460 km2) according to the 2010 United States census), six-county metropolitan statistical area (population of 5,322,219 in an area of 3,913 square miles [10,130 km2] as of the 2010 census), and a nine-county Combined Statistical Area (population of 5.3 million within 5,814 square miles [15,060 km2] as of 2010[update]).[113][114][115]

Topography

[edit]According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 142.87 square miles (370.03 km2), of which 138.75 square miles (359.36 km2) is land and 4.12 square miles (10.67 km2) is water.[116] Detroit is the principal city in Metro Detroit and Southeast Michigan. It is situated in the Midwestern United States and the Great Lakes region.[117]

The Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge is the only international wildlife preserve in North America and is uniquely located in the heart of a major metropolitan area. The refuge includes islands, coastal wetlands, marshes, shoals, and waterfront lands along 48 miles (77 km) of the Detroit River and western Lake Erie shoreline.[118]

The city slopes gently from the northwest to southeast on a till plain composed largely of glacial and lake clay. The most notable topographical feature in the city is the Detroit Moraine, a broad clay ridge on which the older portions of Detroit and Windsor are located, rising approximately 62 feet (19 m) above the river at its highest point.[119] The highest elevation in the city is directly north of Gorham Playground on the northwest side approximately three blocks south of 8 Mile Road, at a height of 675 to 680 feet (206 to 207 m).[120] Detroit's lowest elevation is along the Detroit River, at a surface height of 572 feet (174 m).[121]

Belle Isle Park is a 982-acre (1.534 sq mi; 397 ha) island park in the Detroit River, between Detroit and Windsor, Ontario. It is connected to the mainland by the MacArthur Bridge. Belle Isle Park contains such attractions as the James Scott Memorial Fountain, the Belle Isle Conservatory, the Detroit Yacht Club on an adjacent island, a half-mile (800 m) beach, a golf course, a nature center, monuments, and gardens. Both the Detroit and Windsor skylines can be viewed at the island's Sunset Point.[122]

Three road systems cross the city: the original French template, with avenues radiating from the waterfront, and true north–south roads based on the Northwest Ordinance township system. The city is north of Windsor, Ontario. Detroit is the only major city along the Canada–U.S. border in which one travels south in order to cross into Canada.[123]

Detroit has four border crossings: the Ambassador Bridge and the Detroit–Windsor tunnel provide motor vehicle thoroughfares, with the Michigan Central Railway Tunnel providing railroad access to and from Canada. The fourth border crossing is the Detroit–Windsor Truck Ferry, near the Windsor Salt Mine and Zug Island. Near Zug Island, the southwest part of the city was developed over a 1,500-acre (610 ha) salt mine that is 1,100 feet (340 m) below the surface. The Detroit salt mine run by the Detroit Salt Company has over 100 miles (160 km) of roads within.[124][125]

Cityscape

[edit]Architecture

[edit]

Seen in panorama, Detroit's waterfront shows a variety of architectural styles. The postmodern Neo-Gothic spires of Ally Detroit Center were designed to refer to the city's Art Deco skyscrapers. Together with the Renaissance Center, these buildings form a distinctive and recognizable skyline. Examples of the Art Deco style include the Guardian Building and Penobscot Building downtown, as well as the Fisher Building and Cadillac Place in the New Center area near Wayne State University. Among the city's prominent structures are United States' largest Fox Theatre, the Detroit Opera House, and the Detroit Institute of Arts, all built in the early 20th century.[126][127]

While the Downtown and New Center areas contain high-rise buildings, the majority of the surrounding city consists of low-rise structures and single-family homes. Outside of the city's core, residential high-rises are found in upper-class neighborhoods such as the East Riverfront, extending toward Grosse Pointe, and the Palmer Park neighborhood just west of Woodward. The University Commons-Palmer Park district in northwest Detroit, near the University of Detroit Mercy and Marygrove College, anchors historic neighborhoods including Palmer Woods, Sherwood Forest, and the University District.[128]

Forty-two significant structures or sites are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Neighborhoods constructed prior to World War II feature the architecture of the times, with wood-frame and brick houses in the working-class neighborhoods, larger brick homes in middle-class neighborhoods, and ornate mansions in upper-class neighborhoods such as Brush Park, Woodbridge, Indian Village, Palmer Woods, Boston-Edison, and others.[129]

Some of the oldest neighborhoods are along the major Woodward and East Jefferson corridors, which formed spines of the city. Some newer residential construction may also be found along the Woodward corridor and in the far west and northeast. The oldest extant neighborhoods include West Canfield and Brush Park. There have been multi-million dollar restorations of existing homes and construction of new homes and condominiums here.[80][130]

The city has one of the United States' largest surviving collections of late 19th- and early 20th-century buildings.[127] Architecturally significant churches and cathedrals in the city include St. Joseph's, Old St. Mary's, the Sweetest Heart of Mary, and the Cathedral of the Most Blessed Sacrament.[126]

The city has substantial activity in urban design, historic preservation, and architecture.[131] A number of downtown redevelopment projects—of which Campus Martius Park is one of the most notable—have revitalized parts of the city. Grand Circus Park and historic district is near the city's theater district; Ford Field, home of the Detroit Lions, and Comerica Park, home of the Detroit Tigers.[126] Little Caesars Arena, a new home for the Detroit Red Wings and the Detroit Pistons, with attached residential, hotel, and retail use, opened in 2017.[132] The plans for the project call for mixed-use residential on the blocks surrounding the arena and the renovation of the vacant 14-story Eddystone Hotel. It will be a part of The District Detroit, a group of places owned by Olympia Entertainment Inc., including Comerica Park and the Detroit Opera House, among others.[133]

The Detroit International Riverfront includes a partially completed three-and-one-half-mile riverfront promenade with a combination of parks, residential buildings, and commercial areas. It extends from Hart Plaza to the MacArthur Bridge, which connects to Belle Isle Park, the largest island park in a U.S. city. The riverfront includes Tri-Centennial State Park and Harbor, Michigan's first urban state park. The second phase is a two-mile (3.2-kilometer) extension from Hart Plaza to the Ambassador Bridge for a total of five miles (8.0 kilometres) of parkway from bridge to bridge. Civic planners envision the pedestrian parks will stimulate residential redevelopment of riverfront properties condemned under eminent domain.[134]

Other major parks include River Rouge (in the southwest side), the largest park in Detroit; Palmer (north of Highland Park) and Chene Park (on the east river downtown).[135]

Neighborhoods

[edit]

Detroit has a variety of neighborhood types. The revitalized Downtown, Midtown, Corktown, New Center areas feature many historic buildings and are high density, while further out, particularly in the northeast and on the fringes,[136] high vacancy levels are problematic, for which a number of solutions have been proposed. In 2007, Downtown Detroit was recognized as the best city neighborhood in which to retire among the United States' largest metro areas by CNNMoney editors.[137]

Lafayette Park is a revitalized neighborhood on the city's east side, part of the Ludwig Mies van der Rohe residential district.[138] The 78-acre (32 ha) development was originally called the Gratiot Park. Planned by Mies van der Rohe, Ludwig Hilberseimer and Alfred Caldwell it includes a landscaped, 19-acre (7.7 ha) park with no through traffic, in which these and other low-rise apartment buildings are situated.[138] Immigrants have contributed to the city's neighborhood revitalization, especially in southwest Detroit.[139] Southwest Detroit has experienced a thriving economy in recent years, as evidenced by new housing, increased business openings and the recently opened Mexicantown International Welcome Center.[140]

The city has numerous neighborhoods consisting of vacant properties resulting in low inhabited density in those areas, stretching city services and infrastructure. These neighborhoods are concentrated in the northeast and on the city's fringes.[136] A 2009 parcel survey found about a quarter of residential lots in the city to be undeveloped or vacant, and about 10% of the city's housing to be unoccupied.[136][141][142] The survey also reported that most (86%) of the city's homes are in good condition with a minority (9%) in fair condition needing only minor repairs.[141][142][143][144]

To deal with vacancy issues, the city has begun demolishing the derelict houses, razing 3,000 of the total 10,000 in 2010,[145] but the resulting low density creates a strain on the city's infrastructure. To remedy this, a number of solutions have been proposed including resident relocation from more sparsely populated neighborhoods and converting unused space to urban agricultural use, including Hantz Woodlands, though the city expects to be in the planning stages for up to another two years.[146][147]

Public funding and private investment have been made with promises to rehabilitate neighborhoods. In April 2008, the city announced a $300 million (~$417 million in 2023) stimulus plan to create jobs and revitalize neighborhoods, financed by city bonds and paid for by earmarking about 15% of the wagering tax.[146] The city's working plans for neighborhood revitalizations include 7-Mile/Livernois, Brightmoor, East English Village, Grand River/Greenfield, North End, and Osborn.[146] Private organizations have pledged substantial funding to the efforts.[148][149] Additionally, the city has cleared a 1,200-acre (490 ha) section of land for large-scale neighborhood construction, which the city is calling the Far Eastside Plan.[150] In 2011, Mayor Dave Bing announced a plan to categorize neighborhoods by their needs and prioritize the most needed services for those neighborhoods.[151]

Parks

[edit]Detroit Parks & Recreation maintains 308 public parks, totaling 4,950 (2,003 ha) acres or about 5.6% of the city's land area. Belle Isle Park, Detroit's largest and most visited park is the largest city-owned island park in the U.S., covering 982 acres (397 ha).

Grand Circus, the city's first municipal park, opened in 1847. In the early 20th century, the city enlisted landscape architect Augustus Woodward to conceive a framework for Detroit's modern parks system. Augustus Woodward's plan for the city imagined grand boulevards, spacious and elegant common parks, and an orderly, hub-and-spoke city layout.[152]

The Huron-Clinton Metropolitan Authority was created in 1940 by the citizens of Southeast Michigan to serve as a regional park system the park system includes 13 parks totaling more than 24,000 acres (97 km2) arranged along the Huron River and Clinton River forming a partial ring around the Detroit metro area.

Climate

[edit]| Detroit, Michigan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Detroit and the rest of southeastern Michigan have a hot-summer humid continental climate (Köppen: Dfa) which is influenced by the Great Lakes like other places in the state;[153][154][155] the city and close-in suburbs are part of USDA Hardiness zone 6b, while the more distant northern and western suburbs generally are included in zone 6a.[156] Winters are cold, with moderate snowfall and temperatures not rising above freezing on an average 44 days annually, while dropping to or below 0 °F (−18 °C) on an average 4.4 days a year; summers are warm to hot with temperatures exceeding 90 °F (32 °C) on 12 days.[157] The warm season runs from May to September. The monthly daily mean temperature ranges from 25.6 °F (−3.6 °C) in January to 73.6 °F (23.1 °C) in July. Official temperature extremes range from 105 °F (41 °C) on July 24, 1934, down to −21 °F (−29 °C) on January 21, 1984; the record low maximum is −4 °F (−20 °C) on January 19, 1994, while, conversely the record high minimum is 80 °F (27 °C) on August 1, 2006, the most recent of five occurrences.[157] A decade or two may pass between readings of 100 °F (38 °C) or higher, which last occurred July 17, 2012. The average window for freezing temperatures is October 20 through April 22, allowing a growing season of 180 days.[157]

Precipitation is moderate and somewhat evenly distributed throughout the year, although the warmer months such as May and June average more, averaging 33.5 inches (850 mm) annually, but historically ranging from 20.49 in (520 mm) in 1963 to 47.70 in (1,212 mm) in 2011.[157] Snowfall, which typically falls in measurable amounts between November 15 through April 4 (occasionally in October and very rarely in May),[157] averages 42.5 inches (108 cm) per season, although historically ranging from 11.5 in (29 cm) in 1881–82 to 94.9 in (241 cm) in 2013–14.[157] A thick snowpack is not often seen, with an average of only 27.5 days with 3 in (7.6 cm) or more of snow cover.[157] Thunderstorms are frequent in the Detroit area. These usually occur during spring and summer.[158]

| Climate data for Detroit (DTW), 1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1874–present[b] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 67 (19) |

73 (23) |

86 (30) |

89 (32) |

95 (35) |

104 (40) |

105 (41) |

104 (40) |

100 (38) |

92 (33) |

81 (27) |

69 (21) |

105 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 53.0 (11.7) |

55.3 (12.9) |

69.3 (20.7) |

79.6 (26.4) |

87.2 (30.7) |

92.6 (33.7) |

93.8 (34.3) |

92.1 (33.4) |

89.3 (31.8) |

80.6 (27.0) |

66.7 (19.3) |

56.1 (13.4) |

95.4 (35.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 32.3 (0.2) |

35.2 (1.8) |

45.9 (7.7) |

58.7 (14.8) |

70.3 (21.3) |

79.7 (26.5) |

83.7 (28.7) |

81.4 (27.4) |

74.4 (23.6) |

62.0 (16.7) |

48.6 (9.2) |

37.2 (2.9) |

59.1 (15.1) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 25.8 (−3.4) |

28.0 (−2.2) |

37.2 (2.9) |

48.9 (9.4) |

60.3 (15.7) |

69.9 (21.1) |

74.1 (23.4) |

72.3 (22.4) |

64.9 (18.3) |

53.0 (11.7) |

41.2 (5.1) |

31.3 (−0.4) |

50.6 (10.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 19.2 (−7.1) |

20.8 (−6.2) |

28.6 (−1.9) |

39.1 (3.9) |

50.2 (10.1) |

60.2 (15.7) |

64.4 (18.0) |

63.2 (17.3) |

55.5 (13.1) |

44.0 (6.7) |

33.9 (1.1) |

25.3 (−3.7) |

42.0 (5.6) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 0.1 (−17.7) |

3.5 (−15.8) |

12.0 (−11.1) |

25.5 (−3.6) |

36.3 (2.4) |

47.3 (8.5) |

54.1 (12.3) |

53.4 (11.9) |

41.6 (5.3) |

31.0 (−0.6) |

19.8 (−6.8) |

8.8 (−12.9) |

−3.7 (−19.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −21 (−29) |

−20 (−29) |

−4 (−20) |

8 (−13) |

25 (−4) |

36 (2) |

42 (6) |

38 (3) |

29 (−2) |

17 (−8) |

0 (−18) |

−11 (−24) |

−21 (−29) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.23 (57) |

2.08 (53) |

2.43 (62) |

3.26 (83) |

3.72 (94) |

3.26 (83) |

3.51 (89) |

3.26 (83) |

3.22 (82) |

2.53 (64) |

2.57 (65) |

2.25 (57) |

34.32 (872) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 14.0 (36) |

12.5 (32) |

6.2 (16) |

1.5 (3.8) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.9 (4.8) |

8.9 (23) |

45.0 (114) |

| Average extreme snow depth inches (cm) | 7.1 (18) |

6.6 (17) |

4.4 (11) |

0.8 (2.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.1 (2.8) |

4.3 (11) |

10.0 (25) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 13.4 | 11.0 | 11.1 | 12.5 | 12.9 | 10.7 | 10.5 | 9.7 | 9.5 | 10.6 | 11.0 | 13.1 | 136.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 10.7 | 9.2 | 5.3 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 2.6 | 8.0 | 37.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74.7 | 72.5 | 70.0 | 66.0 | 65.3 | 67.3 | 68.5 | 71.5 | 73.4 | 71.6 | 74.6 | 76.7 | 71.0 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 16.2 (−8.8) |

17.6 (−8.0) |

25.9 (−3.4) |

35.1 (1.7) |

45.7 (7.6) |

55.6 (13.1) |

60.4 (15.8) |

59.7 (15.4) |

53.2 (11.8) |

41.4 (5.2) |

32.4 (0.2) |

21.9 (−5.6) |

38.7 (3.7) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 119.9 | 138.3 | 184.9 | 217.0 | 275.9 | 301.8 | 317.0 | 283.5 | 227.6 | 176.0 | 106.3 | 87.7 | 2,435.9 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 41 | 47 | 50 | 54 | 61 | 66 | 69 | 66 | 61 | 51 | 36 | 31 | 55 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1.2 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 5.4 | 6.9 | 8.0 | 8.2 | 7.1 | 5.3 | 3.1 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 4.4 |

| Source 1: NOAA (relative humidity, dew point, and sun 1961–1990)[157][159][160] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: UV Index Today (1995 to 2022)[161] | |||||||||||||

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

See or edit raw graph data.

| Climate data for Detroit | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean No. of days with Maximum temperature => 90.0 °F (32.2 °C) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

| Mean No. of days with Minimum temperature => 68.0 °F (20.0 °C) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 |

| Mean No. of days with Minimum temperature <= 32.0 °F (0.0 °C) | 27 | 25 | 21 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 14 | 24 | 120 |

| Mean No. of days with Maximum temperature <= 32.0 °F (0.0 °C) | 16 | 12 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 42 |

| Mean No. of days with snow depth => 0.1 in (0.25 cm) | 17 | 14 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 48 |

| Average sea temperature °F (°C) | 33.6 (0.9) |

32.7 (0.4) |

33.4 (0.8) |

39.7 (4.3) |

48.9 (9.4) |

63.9 (17.7) |

74.7 (23.7) |

75.4 (24.1) |

70.5 (21.4) |

60.3 (15.7) |

48.6 (9.2) |

38.1 (3.4) |

51.7 (10.9) |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 9.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 14.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 12.2 |

| Average Ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4.8 |

| Source 1: NWS (1991–2020)[162] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2 : Weather Atlas (daylight-UV-water temperature) [163] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1820 | 1,422 | — | |

| 1830 | 2,222 | 56.3% | |

| 1840 | 9,102 | 309.6% | |

| 1850 | 21,019 | 130.9% | |

| 1860 | 45,619 | 117.0% | |

| 1870 | 79,577 | 74.4% | |

| 1880 | 116,340 | 46.2% | |

| 1890 | 205,876 | 77.0% | |

| 1900 | 285,704 | 38.8% | |

| 1910 | 465,766 | 63.0% | |

| 1920 | 993,678 | 113.3% | |

| 1930 | 1,568,662 | 57.9% | |

| 1940 | 1,623,452 | 3.5% | |

| 1950 | 1,849,568 | 13.9% | |

| 1960 | 1,670,144 | −9.7% | |

| 1970 | 1,511,482 | −9.5% | |

| 1980 | 1,203,368 | −20.4% | |

| 1990 | 1,027,974 | −14.6% | |

| 2000 | 951,270 | −7.5% | |

| 2010 | 713,777 | −25.0% | |

| 2020 | 639,111 | −10.5% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 633,218 | [4] | −0.9% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[164] 2010–2020[9] | |||

In the 2020 United States census, the city had 639,111 residents, ranking it the 27th-most populous city in the US.[165][166] Of the large shrinking cities in the US, Detroit has had the most dramatic decline in the population of the past 70 years (down 1,210,457) and the second-largest percentage decline (down 65.4%). In 1950, Detroit was the fourth-largest city in the US behind New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia. While the drop in Detroit's population has been ongoing since 1950, the most dramatic period was the significant 25% decline between the 2000 and 2010 census.[166]

Detroit's 639,111 residents represent 269,445 households, and 162,924 families residing in the city. The population density was 5,144.3 people per square mile (1,986.2 people/km2). There were 349,170 housing units at an average density of 2,516.5 units per square mile (971.6 units/km2). Of the 269,445 households, 34.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 21.5% were married couples living together, 31.4% had a female householder with no husband present, 39.5% were non-families, 34.0% were made up of individuals, and 3.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.59, and the average family size was 3.36.

There was a wide distribution of age in the city, with 31.1% under the age of 18, 9.7% from 18 to 24, 29.5% from 25 to 44, 19.3% from 45 to 64, and 10.4% 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 83.5 males.

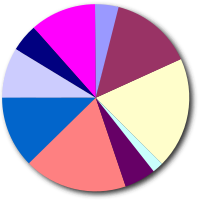

Religion

[edit]According to a 2014 study, 67% of the population of the city identified themselves as Christians, with 49% professing attendance at Protestant churches, and 16% professing Roman Catholic beliefs,[167][168] while 24% claim no religious affiliation. Other religions collectively make up about 8% of the population.

Income and employment

[edit]The loss of industrial and working-class jobs in the city has resulted in high rates of poverty and associated problems.[169] From 2000 to 2009, the city's estimated median household income fell from $29,526 to $26,098.[citation needed] As of 2010[update], the mean income of Detroit is below the overall U.S. average by several thousand dollars. Of every three Detroit residents, one lives in poverty. Luke Bergmann, author of Getting Ghost: Two Young Lives and the Struggle for the Soul of an American City, said in 2010, "Detroit is now one of the poorest big cities in the country".[170]

In the 2018 American Community Survey, median household income in the city was $31,283, compared with the median for Michigan of $56,697.[171] The median income for a family was $36,842, well below the state median of $72,036.[172] 33.4% of families had income at or below the federally defined poverty level. Out of the total population, 47.3% of those under the age of 18 and 21.0% of those 65 and older had income at or below the federally defined poverty line.[173]

| Area | Number of house- holds |

Median House- hold Income |

Per Capita Income |

Percent- age in poverty |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detroit City | 263,688 | $30,894 ( |

$18,621 ( |

35.0% ( |

| Wayne County, MI | 682,282 | $47,301 | $27,282 | 19.8% |

| United States | 120,756,048 | $62,843 | $34,103 | 11.4% |

Race and ethnicity

[edit]| Historical Racial Composition | 2020[175] | 2010[176] | 1990[55] | 1970[55] | 1950[55] | 1940[55] | 1930[55] | 1920[55] | 1910[55] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 14.7% | 10.6% | 21.6% | 55.5% | 83.6% | 90.7% | 92.2% | 95.8% | 98.7% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 10.1% | 7.8% | 20.7% | 54.0%[c] | — | 90.4% | — | — | — |

| Black or African American | 77.7% | 82.7% | 75.7% | 43.7% | 16.2% | 9.2% | 7.7% | 4.1% | 1.2% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 8.0% | 6.8% | 2.8% | 1.8%[c] | — | 0.3% | — | — | — |

| Asian | 1.6% | 1.1% | 0.8% | 0.3% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | — |

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 1960[177] | Pop 1970[178] | Pop 1980[179] | Pop 1990[180] | Pop 2000[181] | Pop 2010[182] | Pop 2020[183] | % 1960 | % 1970 | % 1980 | % 1990 | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 1,182,970 | 838,877 | 402,077 | 212,278 | 99,921 | 55,604 | 60,770 | 70.83% | 55.50% | 33.41% | 20.65% | 10.50% | 7.79% | 10.10% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 482,223 | 660,428 | 754,274 | 774,529 | 771,966 | 586,573 | 493,212 | 28.87% | 43.69% | 62.68% | 75.35% | 81.15% | 82.18% | 77.17% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | N/A | N/A | 3,420 | 3,305 | 2,572 | 1,927 | 1,399 | N/A | N/A | 0.28% | 0.32% | 0.27% | 0.27% | 0.22% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 4,206 | 7,392 | 6,353 | 8,085 | 9,135 | 7,436 | 10,085 | 0.25% | 0.49% | 0.53% | 0.79% | 0.96% | 1.04% | 1.58% |

| Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian alone (NH) | N/A | N/A | 268 | N/A | 169 | 82 | 111 | N/A | N/A | 0.02% | N/A | 0.02% | 0.01% | 0.02% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 745 | 4,785 | 8,006 | 1,304 | 1,676 | 994 | 3,066 | 0.04% | 0.32% | 0.67% | 0.13% | 0.18% | 0.14% | 0.48% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 18,664 | 12,482 | 19,199 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1.96% | 1.75% | 3.00% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | N/A | N/A | 28,970 | 28,473 | 47,167 | 48,679 | 51,269 | N/A | N/A | 2.41% | 2.77% | 4.96% | 6.82% | 8.02% |

| Total | 1,670,144 | 1,511,482 | 1,203,368 | 1,027,974 | 951,270 | 713,777 | 639,111 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

Beginning with the rise of the automobile industry, Detroit's population increased more than sixfold during the first half of the 20th century as an influx of European, Middle Eastern (Lebanese, Assyrian/Chaldean), and Southern migrants brought their families to the city.[184] With this economic boom following World War I, the African American population grew from a mere 6,000 in 1910[185] to more than 120,000 by 1930.[186] Perhaps one of the most overt examples of neighborhood discrimination occurred in 1925 when African American physician Ossian Sweet found his home surrounded by an angry mob of his hostile white neighbors violently protesting his new move into a traditionally white neighborhood. Sweet and ten of his family members and friends were put on trial for murder as one of the mob members throwing rocks at the newly purchased house was shot and killed by someone firing out of a second-floor window.[187]

Detroit has a relatively large Mexican-American population. In the early 20th century, thousands of Mexicans came to Detroit to work in agricultural, automotive, and steel jobs. During the Mexican Repatriation of the 1930s many Mexicans in Detroit were willingly repatriated or forced to repatriate. By the 1940s much of the Mexican community began to settle what is now Mexicantown.[188] Immigration from Jalisco significantly increased the Latino population in the 1990s. By 2010 Detroit had 48,679 Hispanics, including 36,452 Mexicans: a 70% increase from 1990.[189] Per the 2023 American Community Survey five-year estimates, the Mexican American population was 35,273 comprising over 75% of the Latino population with Puerto Ricans as the next largest group at 5,887.[190]

After World War II, many people from Appalachia also settled in Detroit. Appalachians formed communities and their children acquired southern accents.[191] Many Lithuanians also settled in Detroit during the World War II era, especially on the city's Southwest side in the West Vernor area,[192] where the renovated Lithuanian Hall reopened in 2006.[193][194]

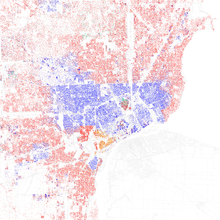

While African Americans in 2020 only comprise 13.5% of Michigan's population, they made up nearly 77.2% of Detroit's population. The next largest population groups were non-Hispanic whites, at 10.1%, and Hispanics, at 8.0%.[183] In 2001, 103,000 Jews, or about 1.9% of the population, were living in the Detroit area.[195] According to the 2010 census, segregation in Detroit has decreased in absolute and relative terms and in the first decade of the 21st century, about two-thirds of the total black population in the metropolitan area resided within the city limits of Detroit.[196][197] The number of integrated neighborhoods increased from 100 in 2000 to 204 in 2010. Detroit also moved down the ranking from number one most segregated city to number four.[198] A 2011 op-ed in The New York Times attributed the decreased segregation rating to the overall exodus from the city, cautioning that these areas may soon become more segregated.

As of 2002, Detroit's percentage of Asians was 1%.[199] There are four areas in Detroit with significant Asian and Asian American populations. Northeast Detroit has a large population of Hmong[200] with a smaller group of Lao people. A portion of Detroit next to eastern Hamtramck includes Bangladeshi Americans, Indian Americans, and Pakistani Americans; nearly all of the Bangladeshi population in Detroit lives in that area. The area north of downtown has transient Asian national origin residents who are university students or hospital workers. Few of them have permanent residency after schooling ends. They are mostly Chinese and Indian but the population also includes Filipinos, Koreans, and Pakistanis. In Southwest Detroit and western Detroit there are smaller, scattered Asian communities.[199][201]

Crime

[edit]| Detroit | |

|---|---|

| Crime rates* (2019) | |

| Violent crimes | |

| Homicide | 41.4 |

| Rape | 143.4 |

| Robbery | 353.3 |

| Aggravated assault | 1,425.8 |

| Total violent crime | 1,965.3 |

| Property crimes | |

| Burglary | 1,027.1 |

| Larceny-theft | 2,235.5 |

| Motor vehicle theft | 1,037.0 |

| Total property crime | 4,299.7 |

Notes *Number of reported crimes per 100,000 population. Source: FBI 2019 UCR data | |

Detroit has gained notoriety for its high amount of crime, having struggled with it for decades. The number of homicides in 1974 was 714.[202][203] The homicide rate in 2022 was the third highest in the nation at 50.0 per 100,000.[204] Downtown typically has lower crime than national and state averages.[205] According to a 2007 analysis, Detroit officials note about 65 to 70 percent of homicides in the city were drug related,[206] with the rate of unsolved murders roughly 70%.[169]

Although the rate of violent crime dropped 11% in 2008,[207] violent crime in Detroit has not declined as much as the national average from 2007 to 2011.[208] The violent crime rate is one of the highest in the United States. Neighborhoodscout.com reported a crime rate of 62.18 per 1,000 residents for property crimes, and 16.73 per 1,000 for violent crimes (compared to national figures of 32 per 1,000 for property crimes and 5 per 1,000 for violent crime in 2008).[209] In 2012, crime in the city was among the reasons for more expensive car insurance.[210]

Areas of the city adjacent to the Detroit River are also patrolled by the United States Border Patrol.[211]

Economy

[edit]| Top city employers as of 2014 Source: Crain's Detroit Business[212] | ||

| Rank | Company or organization | # |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Detroit Medical Center | 11,497 |

| 2 | City of Detroit | 9,591 |

| 3 | Rocket Mortgage | 9,192 |

| 4 | Henry Ford Health System | 8,807 |

| 5 | Detroit Public Schools | 6,586 |

| 6 | U.S. Government | 6,308 |

| 7 | Wayne State University | 6,023 |

| 8 | Chrysler | 5,426 |

| 9 | Blue Cross Blue Shield | 5,415 |

| 10 | General Motors | 4,327 |

| 11 | State of Michigan | 3,911 |

| 12 | DTE Energy | 3,700 |

| 13 | St. John Providence Health System | 3,566 |

| 14 | U.S. Postal Service | 2,643 |

| 15 | Wayne County | 2,566 |

| 16 | MGM Grand Detroit | 2,551 |

| 17 | MotorCity Casino | 1,973 |

| 18 | Compuware | 1,912 |

| 19 | Detroit Diesel | 1,685 |

| 20 | Greektown Casino | 1,521 |

| 21 | Comerica | 1,194 |

| 22 | Deloitte | 942 |

| 23 | Johnson Controls | 760 |

| 24 | PwC | 756 |

| 25 | Ally Financial | 715 |

Several major corporations are based in the city, including three Fortune 500 companies. The most heavily represented sectors are manufacturing (particularly automotive), finance, technology, and health care. The most significant companies based in Detroit include General Motors, Rocket Mortgage, Ally Financial, Compuware, Shinola, American Axle, Little Caesars, DTE Energy, Lowe Campbell Ewald, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, and Rossetti Architects.

About 80,500 people work in downtown Detroit, comprising one-fifth of the city's employment base.[213][214] Aside from the numerous Detroit-based companies listed above, downtown contains large offices for Comerica, Chrysler, Fifth Third Bank, HP Enterprise, Deloitte, PricewaterhouseCoopers, KPMG, and Ernst & Young. Ford Motor Company is in the adjacent city of Dearborn.[215]

Thousands more employees work in Midtown, north of the central business district. Midtown's anchors are the city's largest single employer Detroit Medical Center, Wayne State University, and the Henry Ford Health System in New Center. Midtown is also home to watchmaker Shinola and an array of small and startup companies. New Center bases TechTown, a research and business incubator hub that is part of the Wayne State University system.[216] Like downtown, Corktown Is experiencing growth with the new Ford Corktown Campus under development.[217][218]

Many downtown employers are relatively new, as there has been a marked trend of companies moving from satellite suburbs into the downtown core.[219] Compuware completed its world headquarters in downtown in 2003. OnStar, Blue Cross Blue Shield, and HP Enterprise Services are at the Renaissance Center. PricewaterhouseCoopers Plaza offices are adjacent to Ford Field, and Ernst & Young completed its office building at One Kennedy Square in 2006. Perhaps most prominently, in 2010, Quicken Loans, one of the largest mortgage lenders, relocated its world headquarters and 4,000 employees to downtown Detroit, consolidating its suburban offices.[220] In July 2012, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office opened its Elijah J. McCoy Satellite Office in the Rivertown/Warehouse District as its first location outside Washington, D.C.'s metropolitan area.[221]

In April 2014, the United States Department of Labor reported the city's unemployment rate at 14.5%.[222]

The city of Detroit and other public–private partnerships have attempted to catalyze the region's growth by facilitating the building and historical rehabilitation of residential high-rises in the downtown, creating a zone that offers many business tax incentives, creating recreational spaces such as the Detroit RiverWalk, Campus Martius Park, Dequindre Cut Greenway, and Green Alleys in Midtown. The city has cleared sections of land while retaining some historically significant vacant buildings in order to spur redevelopment;[223] even though it has struggled with finances, the city issued bonds in 2008 to provide funding for ongoing work to demolish blighted properties.[146] Two years earlier, downtown reported $1.3 billion in restorations and new developments which increased the number of construction jobs in the city.[80] In the decade prior to 2006, downtown gained more than $15 billion in new investment from private and public sectors.[224]

Despite the city's recent financial issues, many developers remain unfazed by Detroit's problems.[225] Midtown is one of the most successful areas within Detroit to have a residential occupancy rate of 96%.[226] Numerous developments have been recently completed or are in various stages of construction. These include the $82 million reconstruction of downtown's David Whitney Building (now an Aloft Hotel and luxury residences), the Woodward Garden Block Development in Midtown, the residential conversion of the David Broderick Tower in downtown, the rehabilitation of the Book Cadillac Hotel (now a Westin and luxury condos) and Fort Shelby Hotel (now Doubletree) also in downtown, and various smaller projects.[227][80]