International Bureau of Weights and Measures

| Bureau International des Poids et Mesures | |

| |

Pavillon de Breteuil in 2017 | |

| Abbreviation | BIPM (from French name) |

|---|---|

| Formation | 20 May 1875 |

| Type | Intergovernmental |

| Location |

|

| Coordinates | 48°49′45.55″N 2°13′12.64″E / 48.8293194°N 2.2201778°E |

Region served | Worldwide |

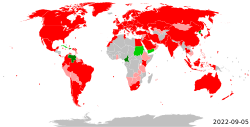

| Membership | 64 member states 37 associate states (see the list) |

Official language | French and English |

Director | Martin Milton |

| Website | www |

The International Bureau of Weights and Measures (French: Bureau International des Poids et Mesures, BIPM) is an intergovernmental organisation, through which its 64 member-states act on measurement standards in areas including chemistry, ionising radiation, physical metrology, as well as the International System of Units (SI) and Coordinated Universal Time (UTC).[1][2] It is based in Saint-Cloud, near Paris, France. The organisation has been referred to as IBWM (from its name in English) in older literature.[note 1]

Structure

[edit]The BIPM is overseen by the International Committee for Weights and Measures (French: Comité international des poids et mesures, CIPM), a committee of eighteen members that meet normally in two sessions per year,[4] which is in turn overseen by the General Conference on Weights and Measures (French: Conférence générale des poids et mesures, CGPM) that meets in Paris usually once every four years, consisting of delegates of the governments of the Member States[5][6] and observers from the Associates of the CGPM. These organs are also commonly referred to by their French initialisms.

History

[edit]The creation of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures followed the Metre Convention of 1875, after the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871),[7] at the initiative of the International Geodetic Association.[8][9] This process began in 1855 with the Exposition Universelle, 1855 in Paris, after the Great Exhibition when the need for international standardization of wheights and measures was identified.[9] It culminated in the first General Conference on Weights and Measures in 1889, when the States parties to the Metre Convention received the standards for the metre and the kilogram.[10]

The American Revolution prompted the foundation of the Survey of the Coast in 1807 and the creation of the Office of Standard Weights and Measures in 1830.[11] During the mid-19th century, the metre was adopted in Khedivate of Egypt an autonomous tributary state of the Ottoman Empire for the cadastre work.[12][13][14] In continental Europe, metrication and a better standardisation of units of measurement marked the Technological Revolution, a period in which German Empire would challenge Britain as the foremost industrial nation in Europe. This was accompanied by development in cartography which was a prerequisite for both military operations and the creation of the infrastructures needed for industrial development such as railways. During the process of unification of Germany, geodesists called for the establishment of an International Bureau of Weights and Measures in Europe.[15][16]

When the metre was choosen as the international unit of length, it was well know that it no longer corresponded to its historical definition.[17][18] Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero, first president of both the International Geodetic Association and the International Committee for Weigths and Measures, took part to the remeasurement and extention of the arc measurement of Delambre and Méchain[19]. At that time, mathematicians like Legendre and Gauss had developed new methods for processing data, including the least squares method which allowed to compare experimental data tainted with observational errors to a mathematical model.[20][21] Moreover the International Bureau of Weights and Measures would have a central role for international geodetic measurements as Charles Édouard Guillaume's discovery of invar minimized the impact of measurement inaccuracies due to temperature systematic errors.[10] The Earth measurements thus underscored the importance of scientific methods at a time when statistics were implemented in geodesy.[21][20] As a leading scientist of his time, Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero was one of the 81 initial members of the International Statistical Institute (ISI) and delegate of Spain to the first ISI session (now called World Statistic Congress) in Rome in 1887.[22][23]

The comparison of the new prototypes of the metre with each other involved the development of special measuring equipment and the definition of a reproducible temperature scale. The BIPM's thermometry work led to the discovery of special alloys of iron–nickel, in particular invar, whose practically negligible coefficient of expansion made it possible to develop simpler baseline measurement methods, and for which its director, the Swiss physicist Charles Édouard Guillaume, was granted the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1920.[24][25] Guillaume's Nobel Prize marked the end of an era in which metrology was leaving the field of geodesy to become an autonomous scientific discipline capable of redefining the metre through technological applications of physics.[26] On the other hand, the fondation of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey by Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler paved the way to the actual definition of the metre, with Charles Sanders Peirce being the first to experimentally link the metre to the wave length of a spectral line. Albert Abraham Michelson soon took up the idea and improved it.[27]

Function

[edit]The BIPM has the mandate to provide the basis for a single, coherent system of measurements throughout the world, traceable to the International System of Units (SI). This task takes many forms, from direct dissemination of units to coordination through international comparisons of national measurement standards (as in electricity and ionising radiation).[citation needed]

Following consultation, a draft version of the BIPM Work Programme is presented at each meeting of the General Conference for consideration with the BIPM budget. The final programme of work is determined by the CIPM in accordance with the budget agreed to by the CGPM.[citation needed]

Currently, the BIPM's main work includes:[28][29][30]

- Making brochures that define the International System of Units.

- Scientific and technical activities carried out in its four departments: chemistry, ionising radiation, physical metrology, and time

- Liaison and coordination work, including providing the secretariat for the CIPM Consultative Committees and some of their Working Groups and for the CIPM MRA, and providing institutional liaison with the other bodies supporting the international quality infrastructure and other international bodies

- Capacity building and knowledge transfer programs to increase the effectiveness within the worldwide metrology community of those Member State and Associates with emerging metrology systems

- A resource centre providing a database and publications for international metrology

The BIPM is one of the twelve member organisations of the International Network on Quality Infrastructure (INetQI), which promotes and implements QI activities in metrology, accreditation, standardisation and conformity assessment.[31]

The BIPM has an important role in maintaining accurate worldwide time of day. It combines, analyses, and averages the official atomic time standards of member nations around the world to create a single, official Coordinated Universal Time (UTC).[32]

Directors

[edit]

Since its establishment, the directors of the BIPM have been:[33][34]

| Name | Country | Mandate | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gilbert Govi | Italy | 1875–1877 | |

| J. Pernet | Switzerland | 1877–1879 | Acting director |

| Ole Jacob Broch | Norway | 1879–1889 | |

| J.-René Benoît | France | 1889–1915 | |

| Charles Édouard Guillaume | Switzerland | 1915–1936 | |

| Albert Pérard | France | 1936–1951 | |

| Charles Volet | Switzerland | 1951–1961 | |

| Jean Terrien | France | 1962–1977 | |

| Pierre Giacomo | France | 1978–1988 | |

| Terry J. Quinn | United Kingdom | 1988–2003 | Honorary director |

| Andrew J. Wallard | United Kingdom | 2004–2010 | Honorary director |

| Michael Kühne | Germany | 2011–2012 | |

| Martin J. T. Milton | United Kingdom | 2013–present |

See also

[edit]- History of the metre

- Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements

- International Organization for Standardization

- Metrologia

- National Institute of Standards and Technology

- Seconds pendulum

- World Metrology Day

- Versailles project on advanced materials and standards

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Staff writer (2024). "Bureau international des poids et mesures (BIPM)". UIA Global Civil Society Database. uia.org. Brussels, Belgium: Union of International Associations. Yearbook of International Organizations Online. Retrieved 1 February 2025.

- ^ "Welcome". BIPM. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ "5 FAH-3 H-310 Organization acronyms". Foreign Affairs Manual. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ "International Committee for Weights and Measures (CIPM)". BIPM. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ Pellet, Alain (2009). Droit international public. LGDJ. p. 574. ISBN 978-2-275-02390-8.

- ^ Schermers, Henry G.; Blokker, Niels M. (2018). International Institutional Law. Brill. pp. 302–303. ISBN 978-90-04-38165-0.

- ^ Débarbat, Suzanne; Quinn, Terry (2019). "Les origines du système métrique en France et la Convention du mètre de 1875, qui a ouvert la voie au Système international d'unités et à sa révision de 2018". Comptes Rendus. Physique (in French). 20 (1–2): 6–21. doi:10.1016/j.crhy.2018.12.002. ISSN 1878-1535.

- ^ Quinn, Terry (2019). "Wilhelm Foerster's Role in the Metre Convention of 1875 and in the Early Years of the International Committee for Weights and Measures". Annalen der Physik. 531 (5): 1800355. doi:10.1002/andp.201800355. ISSN 1521-3889.

- ^ a b Quinn, Terry (2012). From artefacts to atoms: the BIPM and the search for ultimate measurement standards. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 14–18, 3–10. ISBN 978-0-19-990991-9.

- ^ a b "History – The BIPM 150". Retrieved 24 January 2025.

- ^ Cajori, Florian (1921). "Swiss Geodesy and the United States Coast Survey". The Scientific Monthly. 13 (2): 117–129. Bibcode:1921SciMo..13..117C. ISSN 0096-3771.

- ^ Jamʻīyah al-Jughrāfīyah al-Miṣrīyah (1876). Bulletin de la Société de géographie d'Égypte. University of Michigan. [Le Caire]. pp. 6–16.

- ^ Ismāʿīl-Afandī Muṣṭafá (1886). Notes biographiques de S.E. Mahmoud Pacha el Falaki (l'astronome), par Ismail-Bey Moustapha et le colonel Moktar-Bey. pp. 10–11.

- ^ Ismāʿīl-Afandī Muṣṭafá (1864). Recherche des coefficients de dilatation et étalonnage de l'appareil à mesurer les bases géodésiques appartenant au gouvernement égyptien / par Ismaïl-Effendi-Moustapha, ...

- ^ Alder, Ken; Devillers-Argouarc'h, Martine (2015). Mesurer le monde: l'incroyable histoire de l'invention du mètre. Libres Champs. Paris: Flammarion. pp. 499–520. ISBN 978-2-08-130761-2.

- ^ Bericht über die Verhandlungen der vom 30. September bis 7. October 1867 zu BERLIN abgehaltenen allgemeinen Conferenz der Europäischen Gradmessung (PDF) (in German). Berlin: Central-Bureau der Europäischen Gradmessung. 1868. pp. 123–134.

- ^ Guillaume, Ed. (1 January 1916). "Le Systeme Metrique est-il en Peril?". L'Astronomie. 30: 244–245. Bibcode:1916LAstr..30..242G. ISSN 0004-6302.

- ^ Hirsch, Adolphe (1892). Comptes-rendus des séances de la Commission permanente de l'Association géodésique internationale réunie à Florence du 8 au 17 octobre 1891 (in French). De Gruyter, Incorporated. pp. 101–109. ISBN 978-3-11-128691-4.

- ^ Guillaume, Ch.-Éd. (1927). La Création du Bureau International des poids et mesures et son œuvre [The creation of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures and its work]. Paris: Gauthier-Villars et Cie. pp. 18–19, 321.

- ^ a b . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 801–813.

- ^ a b "Mesure du 1er mètre : une erreur qui changea le monde". Techniques de l'Ingénieur (in French). Retrieved 30 March 2025.

- ^ Soler, T. (1 February 1997). "A profile of General Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero: first president of the International Geodetic Association". Journal of Geodesy. 71 (3): 176–188. doi:10.1007/s001900050086. ISSN 1432-1394.

- ^ [webmastergep@unav.es], Izaskun Martínez. "Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero (Grupo de Estudios Peirceanos)". www.unav.es. Archived from the original on 26 December 2024. Retrieved 17 February 2025.

- ^ "Nobel Prize in Physics 1920". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 2 April 2025.

- ^ Guillaume, C.-H.-Ed (1 January 1906). "La mesure rapide des bases géodésiques". Journal de Physique Théorique et Appliquée. 5: 242–263. doi:10.1051/jphystap:019060050024200.

- ^ "BIPM – la définition du mètre". www.bipm.org. Archived from the original on 30 April 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Crease, Robert P. (1 December 2009). "Charles Sanders Peirce and the first absolute measurement standard". Physics Today. 62 (12): 39–44. Bibcode:2009PhT....62l..39C. doi:10.1063/1.3273015. ISSN 0031-9228.

- ^ Wallard, Andrew J. (March 2006). "The International System of Units (SI brochure (EN)): 8th edition, 2006" (PDF).

- ^ "BIPM: Our work programme". BIPM. Archived from the original on 30 May 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ Cai, Juan (Ada). "The Case of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM)" (PDF). oecd.org. OECD. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ "International Network on Quality Infrastructure". INetQI. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ "Time Coordinated Universal Time (UTC)". BIPM. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ "Directors of the BIPM since 1875". Bureau International des Poids et Mesures. 2018. Archived from the original on 27 March 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ "NPL Fellow, Dr Martin Milton, is new Director at foundation of world's measurement system". QMT News. Quality Manufacturing Today. August 2012. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

External links

[edit] Media related to International Bureau of Weights and Measures at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to International Bureau of Weights and Measures at Wikimedia Commons- Official website