Chlorite

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Chlorite

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.123.477 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| ClO− 2 | |

| Molar mass | 67.452 |

| Conjugate acid | Chlorous acid |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

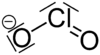

The chlorite ion, or chlorine dioxide anion, is the halite with the chemical formula of ClO−

2. A chlorite (compound) is a compound that contains this group, with chlorine in the oxidation state of +3. Chlorites are also known as salts of chlorous acid.

Compounds

[edit]The free acid, chlorous acid HClO2, is the least stable oxoacid of chlorine and has only been observed as an aqueous solution at low concentrations. Since it cannot be concentrated, it is not a commercial product. The alkali metal and alkaline earth metal compounds are all colorless or pale yellow, with sodium chlorite (NaClO2) being the only commercially important chlorite. Heavy metal chlorites (Ag+, Hg+, Tl+, Pb2+, and also Cu2+ and NH+

4) are unstable and decompose explosively with heat or shock.[1]

Sodium chlorite is derived indirectly from sodium chlorate, NaClO3. First, the explosively unstable gas chlorine dioxide, ClO2 is produced by reducing sodium chlorate with a suitable reducing agent such as methanol, hydrogen peroxide, hydrochloric acid or sulfur dioxide.

Structure and properties

[edit]The chlorite ion adopts a bent molecular geometry, due to the effects of the lone pairs on the chlorine atom, with an O–Cl–O bond angle of 111° and Cl–O bond lengths of 156 pm.[1] Chlorite is the strongest oxidiser of the chlorine oxyanions on the basis of standard half cell potentials.[2]

| Ion | Acidic reaction | E° (V) | Neutral/basic reaction | E° (V) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypochlorite | H+ + HOCl + e− → 1⁄2 Cl2(g) + H2O | 1.63 | ClO− + H2O + 2 e− → Cl− + 2 OH− | 0.89 |

| Chlorite | 3 H+ + HOClO + 3 e− → 1⁄2 Cl2(g) + 2 H2O | 1.64 | ClO− 2 + 2 H2O + 4 e− → Cl− + 4 OH− |

0.78 |

| Chlorate | 6 H+ + ClO− 3 + 5 e− → 1⁄2 Cl2(g) + 3 H2O |

1.47 | ClO− 3 + 3 H2O + 6 e− → Cl− + 6 OH− |

0.63 |

| Perchlorate | 8 H+ + ClO− 4 + 7 e− → 1⁄2 Cl2(g) + 4 H2O |

1.42 | ClO− 4 + 4 H2O + 8 e− → Cl− + 8 OH− |

0.56 |

Uses

[edit]The most important chlorite is sodium chlorite (NaClO2), used in the bleaching of textiles, pulp, and paper. However, despite its strongly oxidizing nature, it is often not used directly, being instead used to generate the neutral species chlorine dioxide (ClO2), normally via a reaction with HCl:

- 5 NaClO2 + 4 HCl → 5 NaCl + 4 ClO2 + 2 H2O

Health risks

[edit]In 2009, the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, or OEHHA, released a public health goal of maintaining amounts lower than 50 parts per billion for chlorite in drinking water[3] after scientists in the state reported that exposure to higher levels of chlorite affect sperm and thyroid function, cause stomach ulcers, and caused red blood cell damage in laboratory animals.[4] Some studies have indicated that at certain levels chlorite may also be carcinogenic.[5]

The federal legal limit in the United States allows chlorite up to levels of 1,000 parts per billion in drinking water, 20 times as much chlorite as California’s public health goal.[6]

Other oxyanions

[edit]Several oxyanions of chlorine exist, in which it can assume oxidation states of −1, +1, +3, +5, or +7 within the corresponding anions Cl−, ClO−, ClO−

2, ClO−

3, or ClO−

4, known commonly and respectively as chloride, hypochlorite, chlorite, chlorate, and perchlorate. These are part of a greater family of other chlorine oxides.

| oxidation state | −1 | +1 | +3 | +5 | +7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| anion named | chloride | hypochlorite | chlorite | chlorate | perchlorate |

| formula | Cl− | ClO− | ClO− 2 |

ClO− 3 |

ClO− 4 |

| structure |

|

|

|

See also

[edit]- Tetrachlorodecaoxide, a chlorite-based drug

- Chloryl, ClO+

2

References

[edit]- ^ a b Greenwood, N.N.; Earnshaw, A. (2006). Chemistry of the elements (2nd ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 861. ISBN 0750633654.

- ^ Cotton, F. Albert; Wilkinson, Geoffrey (1988), Advanced Inorganic Chemistry (5th ed.), New York: Wiley-Interscience, p. 564, ISBN 0-471-84997-9

- ^ "Final Public Health Goal for Chlorite". oehha.ca.gov. Retrieved 2023-08-08.

- ^ Group, Environmental Working. "EWG's Tap Water Database: Contaminants in Your Water". www.ewg.org. Retrieved 2023-08-08.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Public Health Goal for Chlorite in Drinking Water" (PDF). oehha.ca.gov. Retrieved 2023-08-08.

- ^ US EPA, OW (2015-10-13). "Stage 1 and Stage 2 Disinfectants and Disinfection Byproducts Rules". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 2023-08-08.

- Kirk-Othmer Concise Encyclopedia of Chemistry, Martin Grayson, Editor, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1985